Yemen: A Genetic Crossroads of Ancient Humanity

Manage episode 459277365 series 3444207

Unveiling the Genetic Mosaic of Yemen

The Arabian Peninsula, with Yemen at its southern end, has long been a focal point of migration, trade, and cultural exchange. While much attention has been paid to early human dispersals out of Africa, Yemen’s role in shaping human history remains understudied. A new study published in Scientific Reports1 takes a closer look at Yemen’s genetic landscape, uncovering millennia of human movement, intermixing, and adaptation.

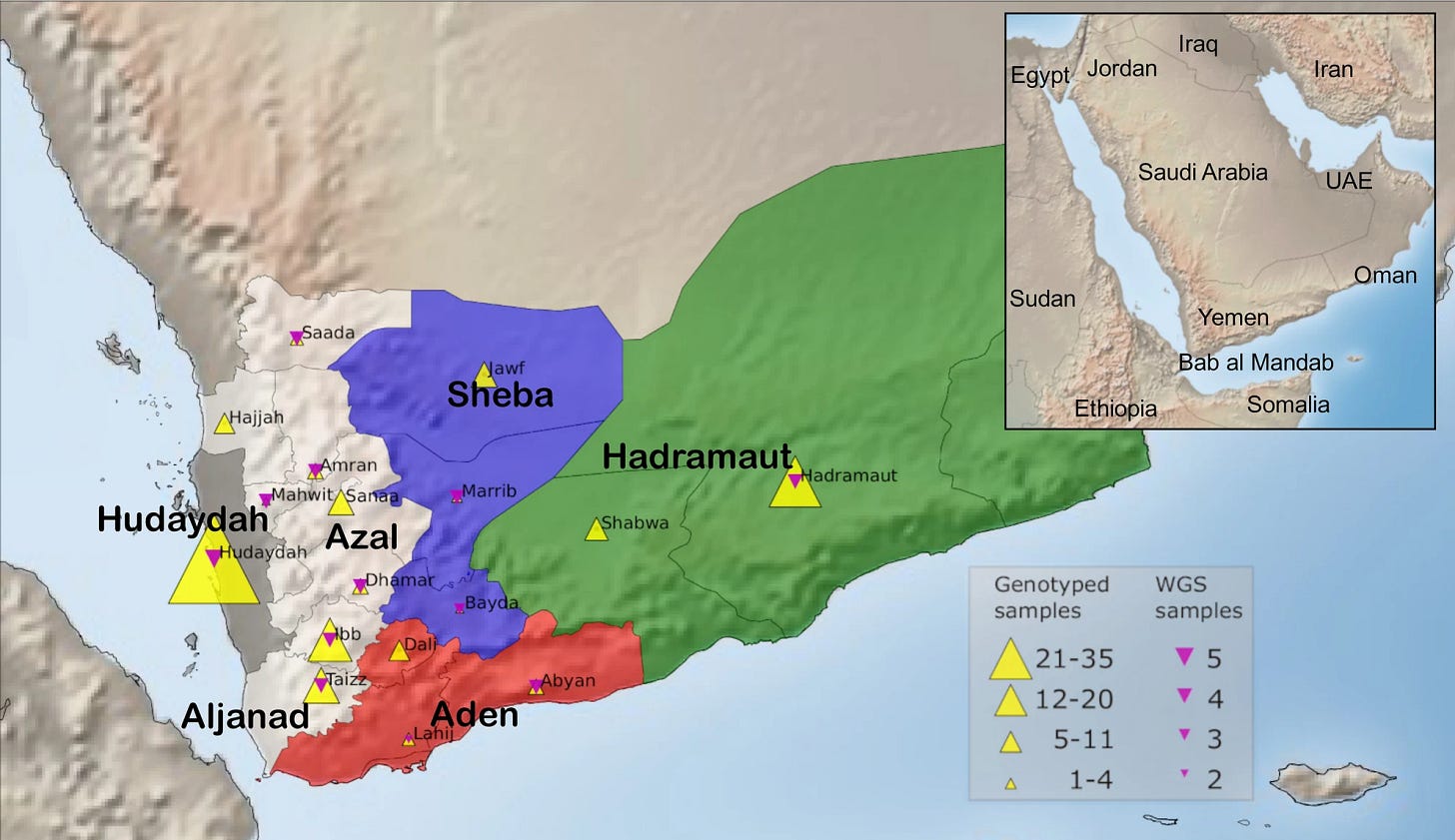

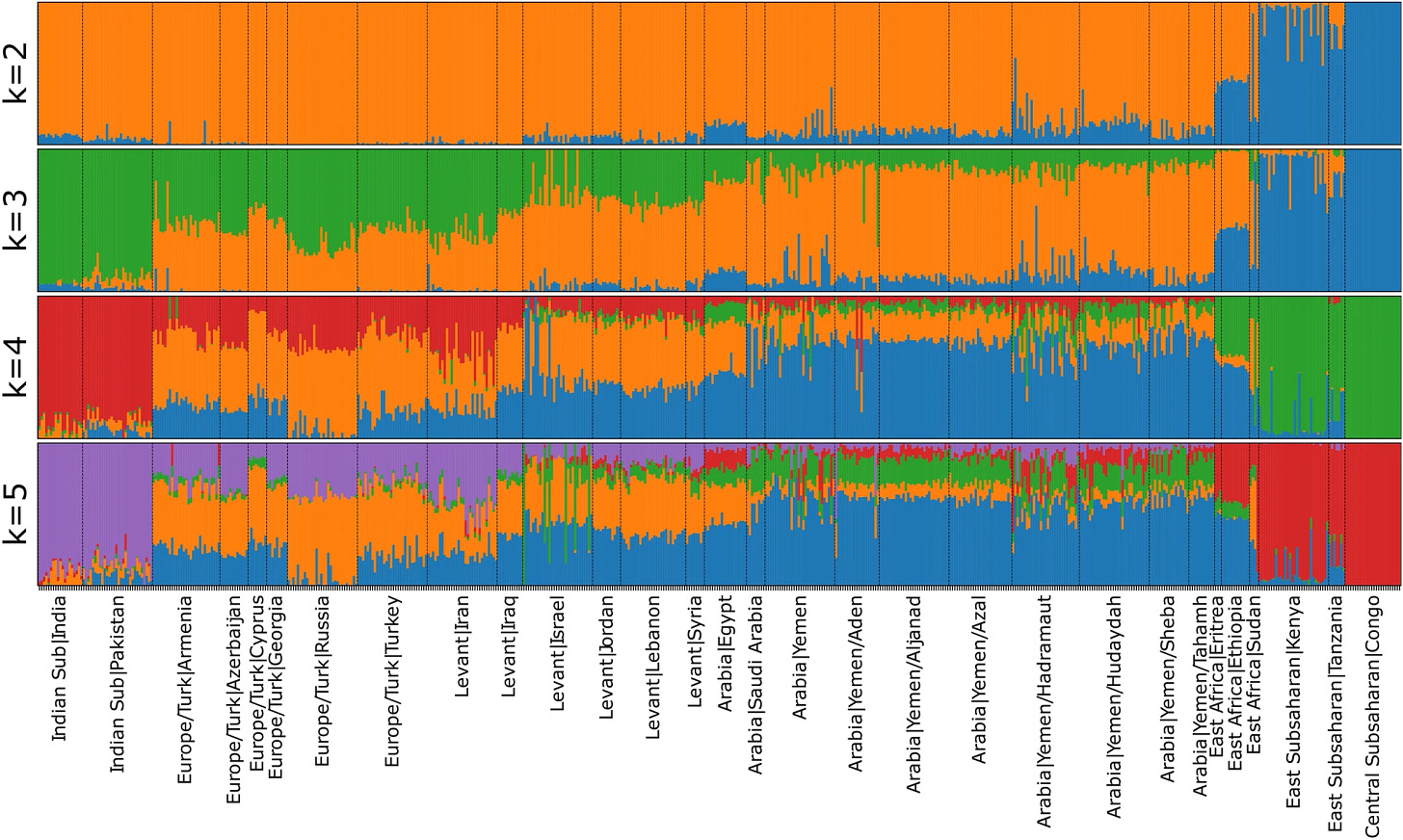

The researchers analyzed genomic data from 46 whole genomes and 169 genotype arrays of Yemeni individuals, contextualizing these findings with data from 351 neighboring populations. Their conclusions shed light on Yemen’s genetic stratification, highlighting its connections to the Levant, Arabia, and East Africa.

“Yemen retains a genetic legacy that reveals the scope of its historical connections, reflecting a remarkable interplay of migration and trade,” the authors note.

Ancient Migrations and Modern Insights

The Last Glacial Maximum and Beyond

The study reveals that as early as 18,000 years ago, during the Last Glacial Maximum, populations from the Levant and Arabia began expanding into Yemen. The melting ice reshaped the landscape, enabling semi-sedentary hunter-gatherers to migrate along coastal and inland routes. These early movements left enduring genetic signatures in Yemeni populations, particularly in the Sheba region.

Later migrations during the Holocene introduced additional genetic diversity. Levantine populations, including those from modern-day Palestine and Syria, brought significant genetic input around 5,000 years ago, likely facilitated by trade networks linking Yemen to Mesopotamia and Anatolia.

“Our analyses reveal gene flow from northern populations into Yemen during pivotal periods of climatic and cultural change,” the study states.

Coastal Connections and African Influences

Yemen and East Africa: A Two-Way Exchange

Yemen’s proximity to the Horn of Africa created a genetic bridge between the two regions, with notable gene flow occurring 750 years ago. This period coincides with heightened trade activity, including the exchange of goods such as spices, incense, and slaves. Coastal regions like Aden and Hudaydah exhibit higher levels of African ancestry, reflecting Yemen’s role in maritime commerce.

Despite this exchange, Yemen remains genetically distinct from East Africa. The study found limited allele sharing between most Yemeni populations and sub-Saharan Africa, suggesting that African influence was concentrated in specific coastal areas.

A Complex Population Structure

Regional Variations Within Yemen

The researchers discovered pronounced genetic stratification within Yemen itself. Coastal populations show greater diversity due to their exposure to maritime trade routes, while inland groups like those from the Sheba region display genetic homogeneity. This variation underscores Yemen’s dual identity as both a gateway and a cultural enclave.

Notably, the study also identified the predominance of Y-chromosome haplogroup J1, which is widespread across Arabia. This haplogroup’s diversity in Yemen suggests a long-standing male lineage in the region, contrasted with mitochondrial DNA haplogroups that highlight African maternal influences.

Challenges and Critiques

While the study is comprehensive, it faces limitations. Sparse sampling from certain Yemeni governorates may overlook local variations, and the reliance on modern genomes means some ancient population events remain underexplored. Furthermore, the researchers acknowledge the ethical complexities of interpreting genetic data tied to historical practices like the slave trade.

The study’s emphasis on broad regional patterns also leaves room for more detailed investigations into Yemen’s genetic microstructure. Future research could incorporate ancient DNA to provide a deeper temporal context.

Yemen as a Genetic Time Capsule

This study positions Yemen as a genetic crossroads, shaped by millennia of migrations and cultural interactions. Its findings highlight the region’s pivotal role in connecting the Levant, Arabia, and Africa, offering a nuanced view of how human populations have adapted to geographic and environmental challenges.

Yemen’s genetic legacy is a testament to its historical importance—a story told not just through archaeological artifacts and historical texts but through the DNA of its people. As genomic technologies advance, Yemen’s role in human history will continue to inspire new discoveries and reshape our understanding of ancient migrations.

Related Research

"Genomic Insights into Arabian Populations"

Explores the genetic diversity across the Arabian Peninsula.

Read more"Out-of-Africa Migration Pathways"

Traces the genetic corridors through Yemen and the Levant.

Read more"Trade and Genetic Exchange in the Red Sea"

Examines the genetic impacts of maritime trade in ancient Yemen.

Read more

Henschel, A., Saif-Ali, R., Al-Habori, M., Kamarul, S. A., Pagani, L., Al Hageh, C., Porcu, E., Taleb, N. N., Platt, D., & Zalloua, P. (2024). Human migration from the Levant and Arabia into Yemen since Last Glacial Maximum. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81615-4

10 episoder